Would the Buddha time the market? Part 2

Part 2 of 2 on a Buddh-ish perspective on how to move cash into the market as interest rates creep lower

Welcome to part 2.

Here we will explore how to move your money from the sidelines into the market—and ponder what the Buddha himself might do with any 'dry powder' in his portfolio—now that interest rates are starting to creep down.

In part 1, we established that timing the market might not be the most skillful approach. You can try it and maybe even get lucky a few times, but you will eventually be humbled. For long-term investing (10, 20, 30 years or more), there’s no better time than right now (other than yesterday) to get your money into the market.

But how to do it?

Throw it all in at once as a lump sum?

Or dole it out over time by dollar-cost averaging?

What would the Buddha do?

I think the Buddha wouldn’t be phased by throwing all his cash into the market as fast as possible. This is a bear-hug embrace of uncertainty / groundlessness, which he was all about.

Some would say this is a foolhardy approach, but the research says otherwise:

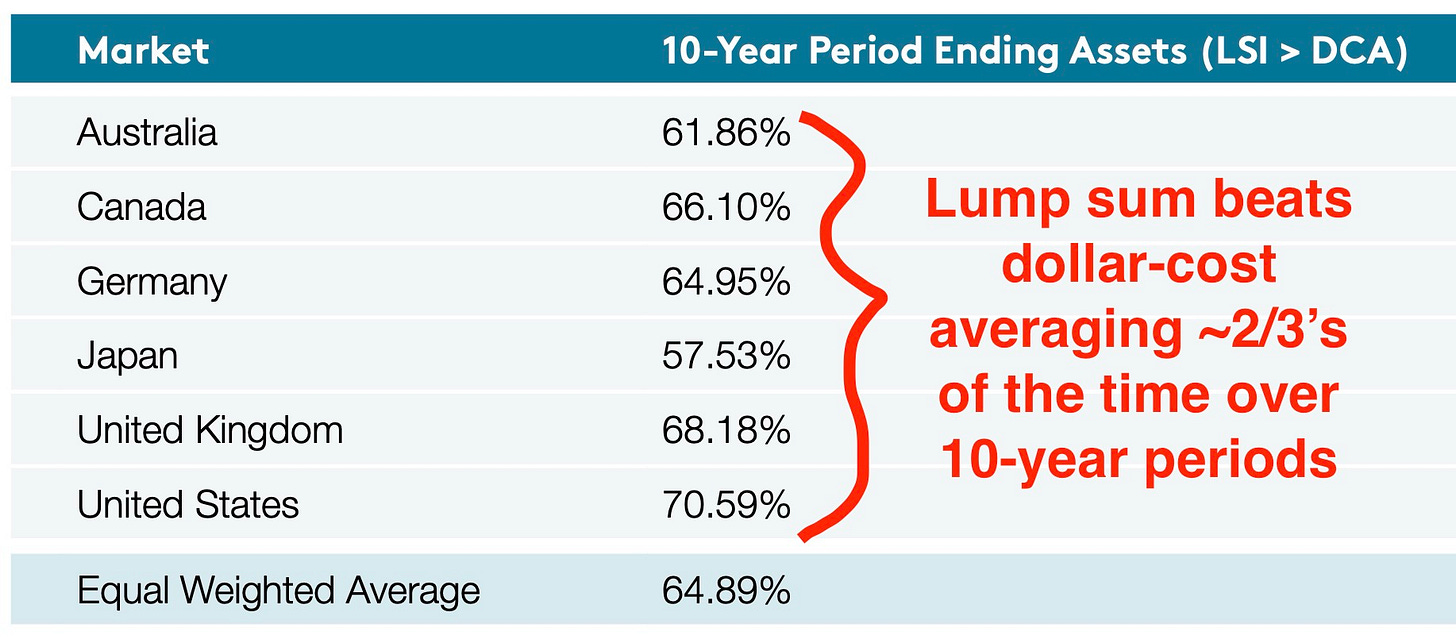

Lump-sum investing (LSI) leads to better long-term portfolio returns than dollar-cost averaging (DCA) about two-thirds of the time:

So that answers that, right? The science confirms that it makes good, rational sense to bear-hug uncertainty. Done and done.

Not so much.

A lump-sum approach might work for an enlightened individual like the Buddha, but the rest of us mortals are subject to cognitive biases, particularly loss aversion, that often lead us to act less than rationally.

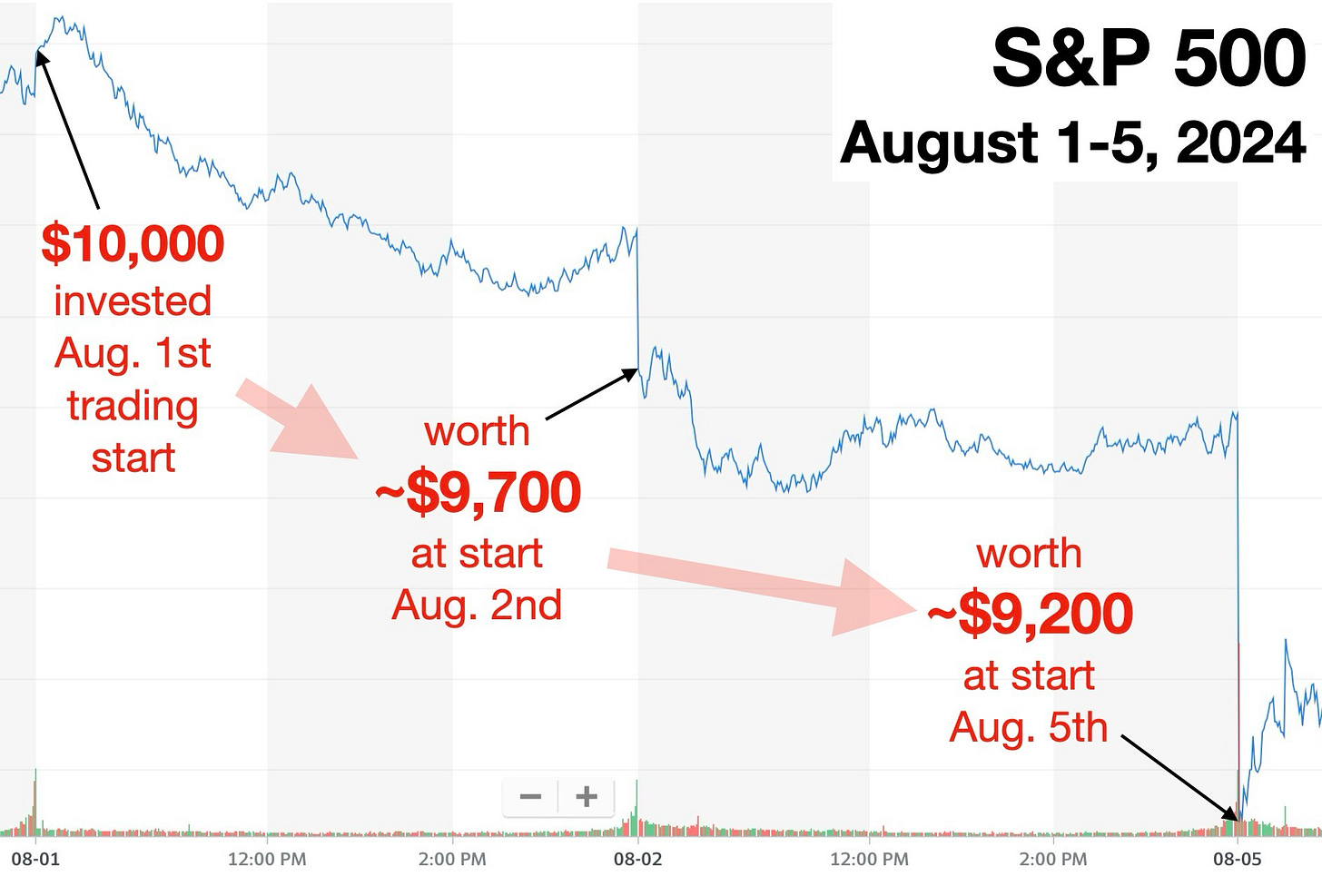

Think about how you’d have felt if you had invested your hard-earned cash into SPY, an S&P500-tracking ETF, at 9:30AM on August 1st, 2024. Over the course of two trading days you would’ve lost 8% of your money (with no telling what further carnage lay in store—fortunately things improved):

This is enough to give me pause. How about you?

As much as I like to consider myself a rational thinker, I lack the intestinal fortitude to do the lump-sum thing.

So instead I dollar-cost average. Basically, I throw some money into the market on a regular-ish basis (every 2-4 weeks) come hell or high water—whether the market happens to be up, down or going sideways.

The stakes seem smaller doing it this way. The down days are easier to stomach.

Taking some of the sting out of investing is why DCA is probably the best investing strategy for most investors. And it has a few other benefits:

DCA is a great strategy for starting investors building a portfolio. It’s never been easier to invest small sums of money to gain broad-market exposure (through low-cost, broad-market ETFs) with online brokerages offering no/low-fee trades and even the option to purchase fractional shares.

DCA, by its nature, means that you can load up on stock shares when they are “on sale.”

I think the Buddha might see additional benefits from DCAing:

DCA encourages regular investing practice in the same way mindfulness is built on time on the meditation cushion.

DCA simplifies/automates investing, freeing up time and energy to dedicate to other pursuits to improve your life and the lives of those around you (or watch Netflix).

DCA promotes equanimity by helping investors get comfortable buying regardless of whether the market is up or down.

Dollar-cost averaging and lump-sum investing both have their appeal and downsides. The choice between the two ultimately comes down to what’s going to work for you in your particular circumstances—whether you’re a novice investor with only small amounts to invest or you happen to be sitting on a chunk of change from an inheritance, etc.

The Buddha was all about what works for people. He encouraged people to take the ‘middle way’ instead of thinking of the world in absolute or inflexible terms, as illustrated by this parable:

Two monks, an elder and his apprentice, are walking together in the countryside. They come to a river and encounter a woman on the riverside. She needs to get to the other side, but doesn’t want to get wet. The elder monk picks up the woman and hikes her over his shoulder and brings her across the water. He puts her down and the two monks continue on their journey. A little bit down the road, the junior monk turns to his colleague and says:

“Master, how could you do that? How could you touch that woman to bring her across the riverside? Doesn't our belief system forbid us from doing that?’

To which the elder replies: “I put down the woman a long time ago and yet you continue to carry her.”

The lesson the elder imparts to his younger colleague is that there are no hard-and-fast rules. The most skillful response to the situation at hand was to help the woman across the river, whatever his rigid belief system had to say about it.

Similarly, when it comes to investing, whether you’re moving sidelined cash into the market, just getting started or managing a hedge fund, the goal is to act in the most skillful way based on careful consideration of the circumstances. There is no one ‘best’ or ‘perfect’ way to do something.

So if you’re happy with a 5% return on your cash (even with the prospect of diminishing returns as rates drop), then stay in cash. But if you’re in it for the long term and want to maximize your chances of wealth, then get that money into play—by dollar-cost averaging, lump-sum investing or, heck, even timing the market.

- The Buddh-i$h Investor

Takeaway points:

Lump-sum investing leads to better long-term portfolio returns two-thirds of the time than dollar-cost averaging.

Dollar-cost averaging may be a more skillful approach than LSI for most investors as it helps minimize loss aversion, get small amounts of cash invested, simplifies/automates investing, and maybe even promotes equanimity.

When it comes to investing and the rest of life, there is no ‘best’ way to do things. Buddhism teaches that decisions and actions are borne out of the situation at hand.

If you’re looking for more:

Dollar Cost Averaging vs. Lump Sum Investing (2020) white paper from PWL Capital’s Ben Felix

And for the TLDR: Ben summarizing the white paper in a snappy 5-minute video

A great overview of DCA from Investopedia: