"I'm just gonna sit here."

What a 1970's revenge movie teaches us about our emotional reactivity

One of my favourite songs is Blood Embrace by Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy and Matt Sweeney. It’s from their 2005 album Superwolf.

Blood is a dirge in the truest sense of the word—mournful, ominous and dripping in inky darkness. It tells the story of a man contemplating how to respond his partner’s test of loyalty—whether violence or surrender:

Does she test me, does she know

That I would sooner turn and go

And find another

If that is what she'd have me do?Or is that what she's waiting on

A pounding down one standing man?

To kiss her in the blood embrace

Of victory- Excerpt from Blood Embrace by Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy & Matt Sweeney

Like a well-built Couch Potato portfolio, Blood is constructed from only a few well-chosen parts: Billy’s exquisitely controlled vocals, Sweeney’s looping guitar, two solitary notes on the piano, and a 70-second audio clip of an unfaithful wife talking to her husband.

I’d been listening to the song for a couple of years before I finally figured out the source of the audio:

Rolling Thunder is a 1977 Vietnam-ploitation1 film starring William Devane and a baby-faced Tommy Lee Jones.

It’s a really interesting movie—surprisingly affecting, but, in equal measure, balls-to-the-wall crazy. The synopsis says it all:

U.S. Air Force Major Charles Rane, a Vietnam War POW, returns home to a changed life, finding his wife engaged to another man and his son distant. After his family is brutally murdered by four outlaws, Rane embarks on a quest for revenge, wielding a shotgun and sharpened hook in place of his right hand. He tracks down and kills every last one of his attackers in a violent shootout in a Mexican bordello.

Yeah, he’s got a hook.

The scene in question takes place not long after Rane returns from Vietnam. It’s late and they’re sitting together in the living room of their marital home. Her nervousness is palpable. His response is jaw-droppingly muted:

“I’m just gonna sit here” says the guy who was left to rot in a POW camp by his country, tortured mercilessly at the hands of his captors, and, upon his safe return home, is greeted by the news that his wife cheated on him.

I don’t know about you, but this would’ve pushed me over the edge. But not Major Charles Rane2. He’s cool as a cucumber about it. As equanimous as the Buddha.

It’s not easy to just sit there

Major Rane’s equanimity in the face of adversity is an example for us all. Think of all the times you’ve reacted in the heat of the moment to some insult or undesired outcome and later regretted it. These heated, automatic reactions—”habitual reactivity” or “habit energy” in Buddhist circles—often just make things worse. Like panic-selling a falling stock and locking in your losses. In nearly all situations, you would’ve been better off following the late Jack Bogle’s timeless investing advice: “Don’t do something, just stand there.”

It’s hard to do nothing though. As humans, we’re programmed to react. To fight or flee, just like our friend in Blood Embrace. This has been baked right into us over millions of years of evolution. Back in the cave-people days, we stayed alive by reacting to threats (e.g., snakes, sabre tooth tigers, etc.). Today, though, our reactions are often out-of-proportion to the threat and end up causing us more trouble than the actual (or perceived) threat itself.

Even when we see the trouble our reactions cause, we can’t seem to stop ourselves from doing them. Time and time again. Our strong emotions, or kleshas as they’re known in Pali, always seem to get the better of us:

Getting angry whenever someone cuts us off in traffic.

Panic-selling when the market takes a dive.

Imbibing too much <insert your poison here> when we’re stressed out.

Continually avoiding the difficult conversations we should be having in our lives.

Et cetera.

Soothe your anger like it’s a baby

This endless cycle of unskillful reactions is called samsara in the Buddhist world. It is a great source of suffering for us human beings.

Buddhism and mindfulness teach us how to break free of samsara and our self-injurious habitual reactivity. We can do this by treating our strong emotions like a baby:

“Suppose a mother is working in the living room and she hears her baby crying. Chances are she puts down whatever she's doing and goes to her baby's room. She picks up the baby and holds it tenderly in her arms. This is exactly what we can do when the energy of anger comes up. Anger is our ailing baby. You must nurture it in order to calm it.”

- Thích Nhất Hạnh, Keeping the Peace

We hold babies gently, we don’t restrain them. We try to understand why they’re crying, not just dismiss them. We give them our full attention.

Try doing the same with your anger, fear, jealousy, craving and other kleshas as the venerable Pema suggests:

Acknowledge the feeling, give it your full, compassionate, even welcoming attention, and even if it’s only for a few seconds, drop the story line about the feeling…Don’t fuel it with concepts or opinions about whether it’s good or bad. Just be present with the sensation. Where is it located in your body? Does it remain the same for very long? Does it shift and change?

- Pema Chödrön, Living Beautifully with Uncertainty and Change

This tenderness, attention and curiosity disarms the strong emotion and creates an opportunity to act in a way that may cause you and others less suffering.

Why? Why? Why? Why? Why?

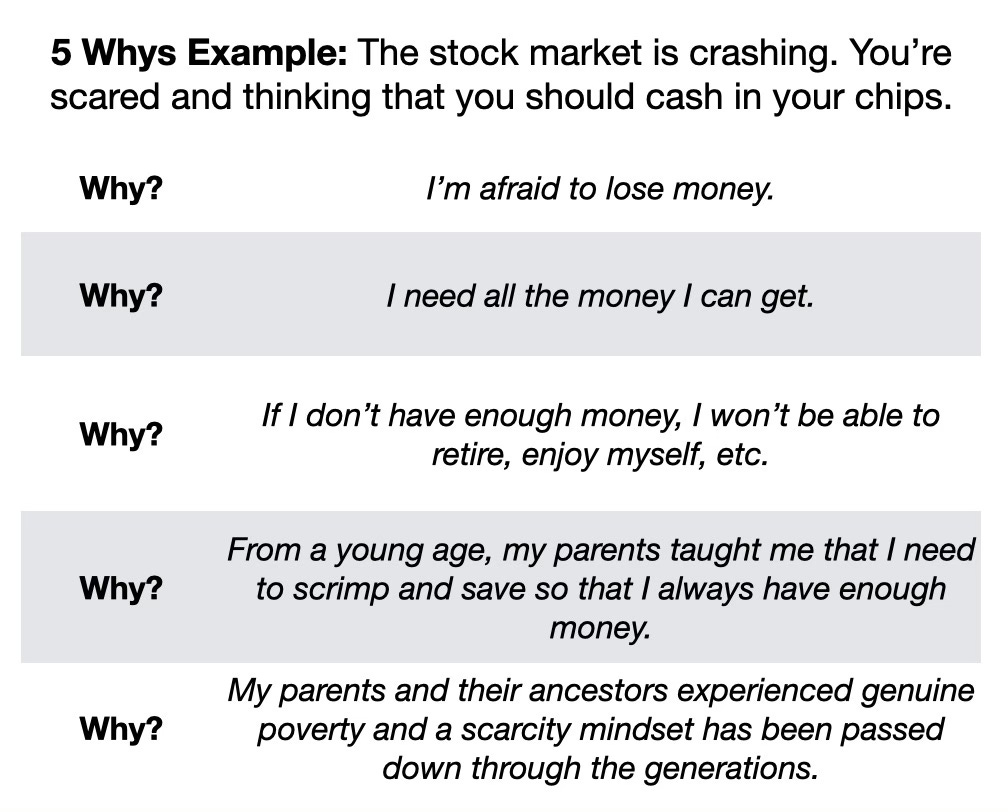

One of the more helpful ways I’ve found to better understand my own kleshas and unskillful reactions is the 5 Whys.

I picked this up from the Toyota company via Buddhist teacher Noah Rasheta.

The 5 Whys approach is used to get at the root cause of a problem by asking the question “Why?” five times. Each successive “Why?” digs a little deeper, in our case, into the thought processes underlying our strong emotions and reactions.

Take this example—and try answering honestly for yourself:

You might have different answers, but that’s not the point. The purpose of the 5 Whys is to pause and reflect on the reasons behind our thoughts and actions. You can try doing this in real-time (for instance, when you’re reacting), but due to the often rapid and intense nature of reactions, you’ll likely end up doing it afterward, as a post-mortem.

It’s not as simple as “they’re an asshole”

Even a brief examination of a regrettable reaction can generate numerous reasons for our actions. Consider the example of snapping at a loved one. They said something you didn’t like, and you became angry at them. Initially, you might justify your reaction by saying, “What an asshole thing to say.” And perhaps it was indeed an inappropriate remark. However, delve deeper into your reaction. Ask yourself why you responded the way you did. Perhaps you’re feeling tired, hungry, or are overly sensitive to criticism. Perhaps something about their tone reminded you of a parent’s anger when you were a child.

Contemplation opens up a Pandora’s box of ‘causes and conditions’ for our actions. It’s not as simple as “they’re an asshole.” That’s merely the tip of the tip of the iceberg.

With a deeper understanding of why Thích Nhất Hạnh’s proverbial baby is crying, you’ll be better equipped to soothe it. Instead of pushing it away, you’ll want to hold it closer. Otherwise, the baby will just keep crying.

Getting comfortable embracing our crying klesha baby is not an easy thing. It’s easier just to flip our lid like we’ve always done.

It’s a lifelong journey fraught with setbacks (like rampages in Mexican bordellos) along the way. With mindful awareness and self-compassion, we hope to gradually progress on the path to enlightenment. We’ll peel away layer after layer to reveal our inner Buddha or Major Charles Rane.

That’s what our friend in Blood Embrace is doing. He’s still deep in contemplation by the end of the song. Instead of lashing out only to regret it later, he’s just sitting there trying to figure himself out.

- The Buddh-i$h Investor

Take home points:

Our automatic reactions, often driven by strong emotions (a.k.a. kleshas), can be a source of great suffering our lives.

Embracing and understanding our strong emotions can help us break free from the endless cycle of unskillful reactions (i.e., samsara).

The “5 Whys” is a technique to understand the root causes of our reactions and to respond with greater wisdom and equanimity.

If you’re looking for more:

Best played at night in a dark room:

Quentin Tarantino referred to Rolling Thunder as “ass-kicking nirvana,” but I don’t think he meant it in a Buddhist sense:

Did I just coin a new term?

Of course, he later goes on a rampage. But said rampage is arguably quite justified (at least in the world of 1970’s revenge movies).