When is a bike no longer a bike?

Making sure to zoom in and zoom out on our portfolios

This used to be a bike.

Two years ago, when I first noticed it chained to a fence near my place, it was a bike. With all its parts.

A week later it was still there, but the front wheel was missing. Then the seat cover disappeared. Then the handlebars. Now it’s barely recognizable as a bicycle.

The question I ask myself every time I walk by now is: When did it stop being a bike?

Once the wheels were gone? The handlebars?

The bike, for lack of a better word, has become something of a Zen koan to me. Along the lines of “What’s the sound of one hand clapping?” or “If a tree falls in the forest and no one’s around to hear it, does it make a sound?”

Koans are stories, phrases or questions that get us thinking about Buddhist concepts. They are, by nature, confusing and open to interpretation. They pose questions that have no answers.

Koans are frustrating for this reason. But that’s the whole point. As human beings, we like when things make sense, when the world seems like it’s in our control. Koans are a middle finger to “making sense.”

Emptiness: Not empty, but very full

My bike koan really has no answer. And that’s the whole point. It is a lesson in the concept of “emptiness” or “no self.”

“Emptiness” is one of those Buddhist terms that seems almost intentionally confusing. To say something is “empty” doesn’t mean that it is devoid of content. It means that the “something” has no discrete essence, nothing that separates it from everything else, no self.

Everything—bikes, weiner dogs, you and me—only exist as a culmination of parts that are each connected to everything else in the world. In other words, we can’t be separate from anything because we only exist because of and in relation to everything else1.

To illustrate, let’s go back to the bike. We call it a “bike” and recognize it as its own discrete entity. But really it’s just a bunch of bike parts assembled together.

Not one of those parts by itself constitutes the bike. And the parts themselves have parts and those parts are made from various materials made in various places by various people. You could go on like this infinitely.

And yet it’s still hard to think of a bike as anything other than a bike.

That’s how are brains are wired. We assign fixed, singular essences to things that are, in reality, always changing and really a billion things all at once.

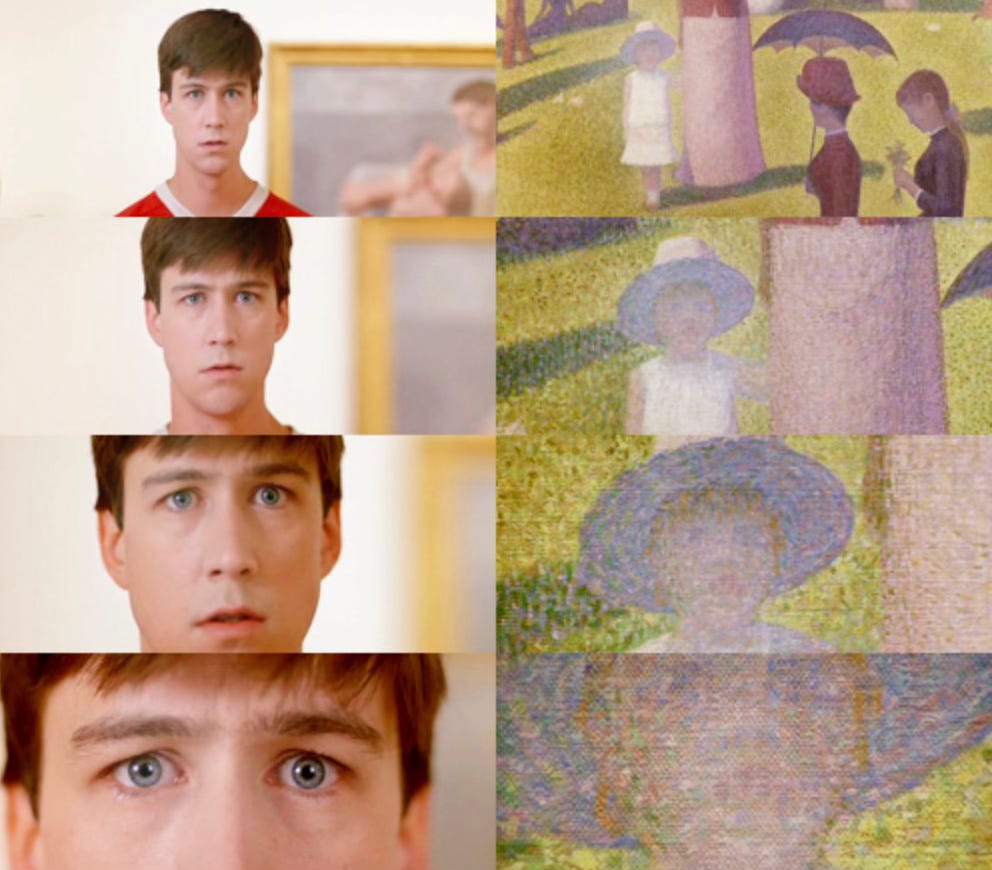

It’s like one of those pointillist paintings. Take a closer look, like Cameron Frye in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, and your mind is blown:

What emptiness teaches us about our portfolios

Our portfolios are like pointillist paintings. They have different parts. And, if you’re an index investor like me, even the parts themselves have many parts. For example, VGRO, one of Vanguard’s portfolio funds (which I’ve been known to hold), includes 13,000 stocks and nearly 20,000 bonds. [Now that’s diversification.]

This is helpful to bear in mind if we ever get too preoccupied with one part of our portfolio. Like a TSLA or NVDA. We can’t forget the other portfolio parts no matter how exciting these news-making investments might be.

We also can’t forget that a portfolio is neither fixed nor permanent. It’s makeup of assets (e.g., stocks, bonds) will change along with the ceaseless shifting of the markets and our evolving financial needs over time. We need to continue rebalancing and critically evaluating the structure of a portfolio with the passage of time: does it match my risk tolerance? Is it allocated appropriately to my age and life situation? When’s the last time I rebalanced? And so on.

It’s also helpful to remind ourselves that, just like they are the culmination of many things, our portfolios themselves are part of a much larger web that is our financial life. A portfolio might be the front wheel, but we also need handlebars, a bike frame, a seat, a will, a power-of-attorney, an estate plan, insurance and the rest of an endless chain of ‘causes and conditions.’

We need to, like Cameron, zoom in on our portfolios to see the pixels, but, at the same time, zoom out to see that it’s just one piece of a much larger, ever-changing puzzle. Or bicycle.

- The Buddh-i$h Investor

Take home points:

Emptiness teaches us that everything is “empty” of a discrete essence. Everything is dependent on everything else in the universe. Nothing exists in isolation.

Considering the “empty” nature of our portfolios reminds us 1) to not get too preoccupied on one particular part (e.g., NVDA) and 2) that portfolios themselves are merely one small aspect of our financial lives.

If you’re looking for more:

Noah Rasheta on emptiness in episode #3 of his Secular Buddhism podcast. [The first five episodes of Noah’s podcast are what got me into Buddhism in the first place! Highly recommended.]

That great scene from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off:

This is the concept of interdependence or dependent origination, which I’ll revisit in another post.