Would the Buddha time the market? Part 1

Part 1 of 2 on a Buddh-ish perspective on how to move cash into the market as interest rates creep lower

Interest rates are starting to come down.

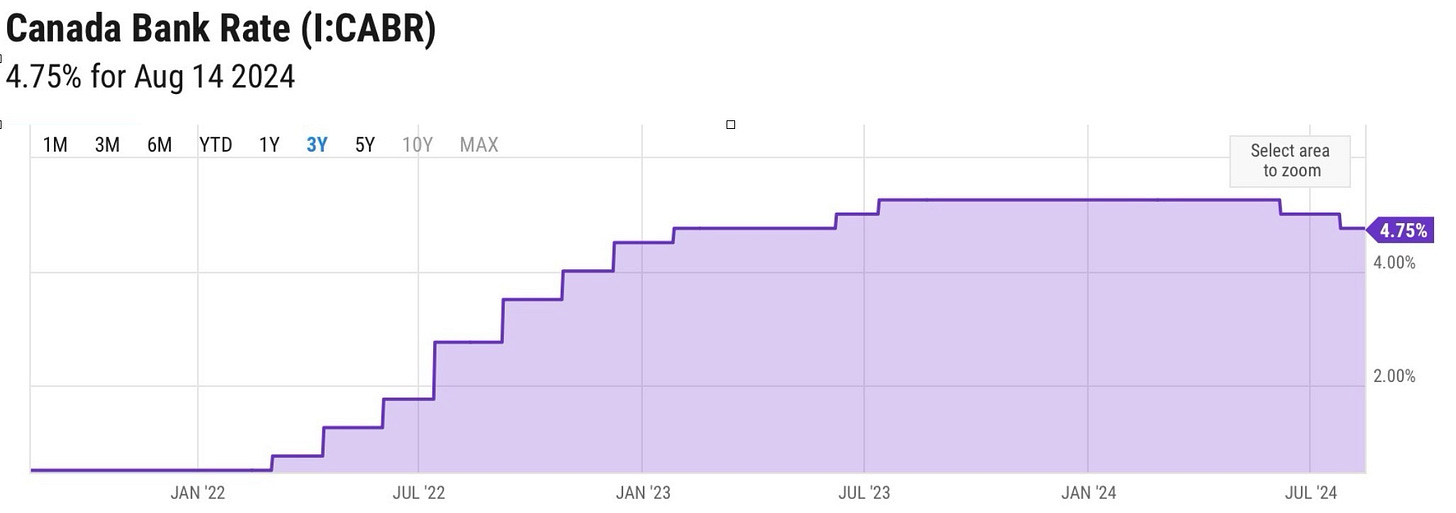

On July 25th, the Bank of Canada announced its second rate drop in the past few months, bringing their overall rate down to 4.75%:

This is a pleasant turn of events for people holding variable mortgages and other forms of debt that bounce around with the bank's interest rate.

For many investors, however, it marks the beginning of the end of easy money.

Investment Savings Accounts (ISA), GICs and money market funds have been a safe place to park and grow cash risk-free over the past year or two. Prior to this, in the ZIRP (Zero Interest Rate Policy) era of the early 2000s onwards, these products have offered investors only a pittance of interest.

However, with the sharp rise of interest rates in the inflationary, post-COVID world of the past 2 years (see above), they’ve been paying out interest of close to 5%. Not too shabby for an essentially zero-risk investment.

The rate drops from the BoC are a signal to many investors, including myself, to shift some1 money from the sidelines into play in the market.

The question I’m grappling with now is:

When should I “pull the trigger” and move money into market?

Maybe you’re grappling with the same question. If so, how are you approaching it? (testing out Substack’s poll feature):

Fortunately, you and I are not the first investors facing this eternal and infernal question of whether to “time the market” or not. It has been robustly studied and there’s a pretty clear winner:

Timing the market is not the answer.

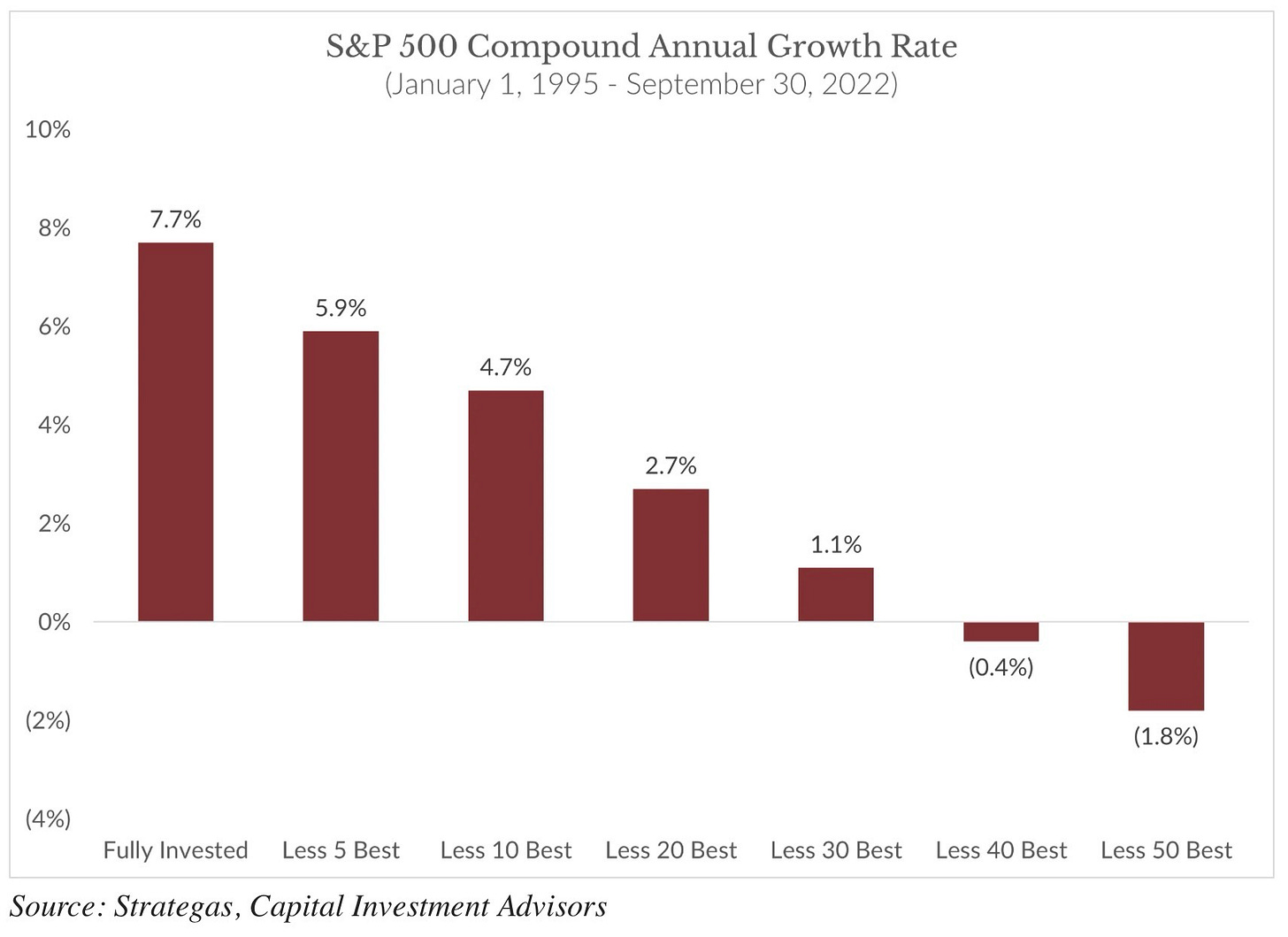

Sure you might get lucky, buying low then watching your portfolio soar in value, but the more likely outcome is that your cash will just sit there… and sit there… and sit there while you wait for the perfect moment. And this can come at a great opportunity cost, which this chart beautifully terrifyingly captures:

There were approximately 7,000 trading days between January 1, 1995 and September 30, 2022. If you had been invested in the S&P500 during the period and managed to miss (by sitting in cash) just 5 of the best “up days”, your long-term returns would be nearly 2% lower (7.7 versus 5.9%).

Another way to look at it: 0.07% of trading days account for nearly 25% of the returns of a 27-year period.

The odds are seriously stacked against investors for nailing those weighty days.

That is, unless your money is already in play—and not warming the bench and waiting for its chance.

This is why not timing the market is the better approach. If you get invested as soon as possible and stay invested for the long-term you will get to experience the benefit of all of those rare up days.

I’ll admit that it’s been a struggle for me to not try to time the market even with this information top of mind. Part of the reason I’m writing this post is to nudge myself to make some trades to get cash reserves into the market.

I’ve found that there’s powerful inertia to overcome. There’s a sense of security that goes along with reliably collecting 5% risk-free. And I, like most human beings, like a sense of security however fleeting or irrational or delusional it might be.

Uncertainty, which Buddhists call groundlessness, makes us very uncomfortable as Pema Chödrön nicely articulates:

“As human beings we share a tendency to scramble for certainty whenever we realize that everything around us is in flux…What a predicament! We seem doomed to suffer simply because we have a deep-seated fear of how things really are.”

Pema Chödrön

There’s a deep irony here. Our suffering actually comes from our ham-fisted attempts to reduce our suffering—by avoiding discomfort, clinging to things that make us feel good and denying uncertainty.

In the case of what to do about my investments in cash, the (“little s”) suffering that I, and other investors in the same situation, face is indecision and cognitive dissonance. My rational mind knows the data and that I’d likely be better off buying into the market, but my irrational lizard brain is caught up in loss aversion. I’m paralyzed by fear of bungling things and losing money. I’m clinging to that sweet 5% interest rate in hopes that it will last forever. All the while it’s starting to crumble beneath my feet.

Noah Rasheta, a Secular Buddhist podcaster/author/teacher, encourages people to “step into” groundlessness. Noah, among other things, is an avid paraglider and spends a lot of time standing at the top of tall mountains. He likens stepping into groundlessness to taking that step off the side of a cliff.

Sure there’s risk to stepping off a cliff, but, when it comes to groundlessness, it’ll hurt more not to.

Noah and his glider will be on my mind when I click “Buy” once the opening market bell chimes on Monday.

- The Buddh-i$h Investor

In part 2 of Would the Buddha time the market?, we will explore whether it makes more sense—from wealth-building and Buddhist perspectives—to invest excess cash as a lump sum or by dollar-cost averaging. Stay tuned!

Key takeaway points:

With interest rates creeping downwards, it's not a bad time to think about moving cash on the sidelines (collecting interest in HISAs, GICs, etc.) into the market.

The best time to move cash into the market is NOW. Timing the market is a fool’s game.

Investing your hard-earned money in the stock market is risky, but sitting on cash long-term is arguably riskier. That said, it’s not easy to turn your back on an assured 5% return to put your money into the ever-volatile stock market.

The market, as with the rest of life, is mired in uncertainty and the only way to minimize suffering (and build wealth) is to embrace the uncertainty and get your money in play.

If you’re looking for more:

On groundlessness:

Noah Rasheta’s powerful discussion of groundlessness from the Secular Buddhism podcast

Pema Chödrön on The Fundamental Ambiguity of Being Human

On market timing:

Ben Carlson has frequently visited the market timing issue over the years. Here are few posts that stand out:

Wes Moss’s article The Perils Of Market Timing: Missing The Best Days In The Market

I should point out that I like to keep at least 5% of my portfolio in cash at all times. This amount has drifted up a bit over the past two years with the more favourable (for interest income—not mortgages) rate environment of the past couple of years. I also let it drift higher after learning in his great book The Psychology of Money that Morgan Housel’s personal cash allocation is 20%. He’s big on emergency funds.